Story: Corals, anemones and jellyfish

Page 4 – Jellyfish

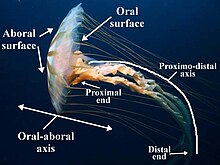

Jellyfish are cnidarian medusae. Jellyfish are members of the class Scyphozoa, which, although widespread in the world’s oceans, includes only about 250 species.

Jellyfish galore

Sudden swarms of jellyfish can be devastating. They can clog the pipes of leisure boats, ships, and power plants. They consume massive amounts of the larvae of commercial fish and shellfish and their food. High densities of jellyfish can literally suffocate the stock in commercial fish farms.

Swimming jellyfish

Swimming jellyfish (scyphozoans) live in sea water and have a reduced or absent polyp phase. New Zealand species have never been properly studied, and several species are probably new to science.

The best-known species around New Zealand include the stinging lion’s-mane jellyfish (Cyanea species) and the moon jelly (Aurelia species). The latter can wash up in large numbers on beaches. It is quite transparent, with four purple sex organs visible through the jelly. Touching the upper surface of the jelly-like bell is safe – it is the tentacles that should be avoided. Moon jellies are responsible for the death of farmed fish in New Zealand, when they are drawn into bays where the fish are penned. The actual cause of death is not certain, but it is thought to be due to nettle-cell irritation and jellyfish mucus coating the fish gills.

Stalked jellyfish

Little is known about the biology of stalked (‘upside-down’) jellyfish, which belong to the class Staurozoa. They can creep and somersault, but cannot swim in typical jellyfish fashion. Only a single species, Craterolophus macrocystis, has been documented in New Zealand waters. Originally collected from Port Chalmers, attached to bladder kelp, it has apparently never been found again. It was about 2.5 centimetres tall and dark green when alive, and therefore well camouflaged. A second stalked jellyfish, Depastromorpha africana, was recently reported in New Zealand waters and an unidentified species of Lipkea has been found on cave walls at the Poor Knights Islands. Fossil members, called conulariids, are known from Paleozoic rocks in New Zealand.

Box jellies

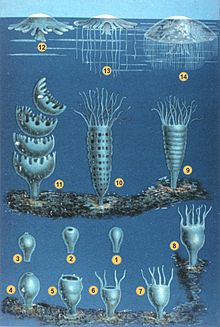

As their name indicates, box jellies are muscular, square-shaped animals. Members of the class Cubozoa, they differ from true jellyfish, having a life cycle that involves total metamorphosis of the polyp into the medusa (jellyfish stage). They also have highly developed eyes. New Zealand does not have a problem with box jellies, but they are a nuisance in Queensland, where the species Chironex fleckeri is the most venomous animal in the world. Only one box jelly species is known from New Zealand – the diminutive Carybdea sivickisi, seen in Cook Strait.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

The

jellyfish that we both admire and hate today, could have stepped out of

a lost world dating back four hundred million years before the dinosaurs.

They are old, primitive creatures, yet so effective that they hold their

own in our modern world. Scientists would be interested to see what they

actually looked like when they first appeared on Earth, but their soft

bodies left few fossil traces. In this article we'll examine the few large

species found in New Zealand waters. But jellyfish are also harbingers

of pollution that kills other marine organisms.

The

jellyfish that we both admire and hate today, could have stepped out of

a lost world dating back four hundred million years before the dinosaurs.

They are old, primitive creatures, yet so effective that they hold their

own in our modern world. Scientists would be interested to see what they

actually looked like when they first appeared on Earth, but their soft

bodies left few fossil traces. In this article we'll examine the few large

species found in New Zealand waters. But jellyfish are also harbingers

of pollution that kills other marine organisms.